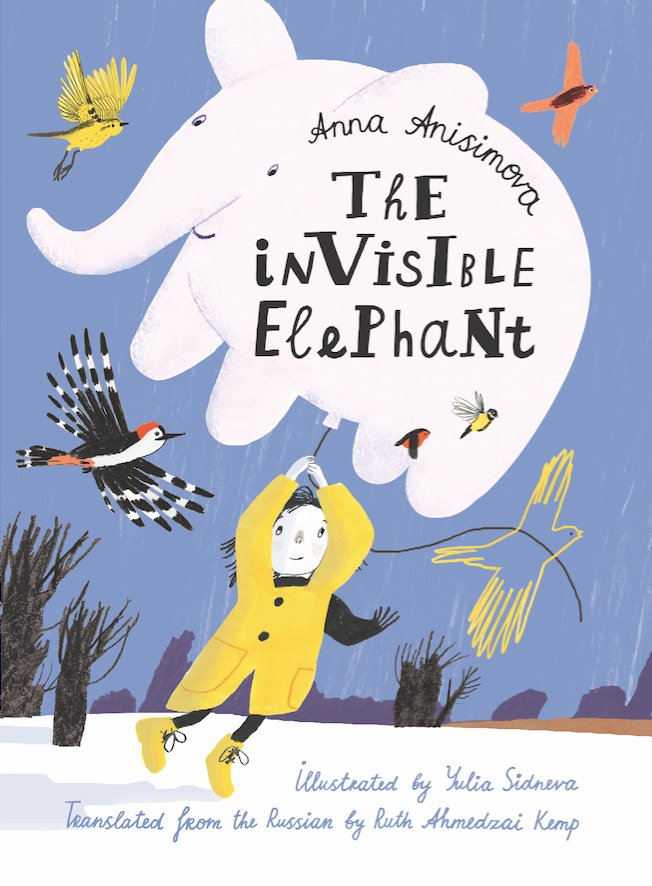

Today World Kid Lit co-editor Jackie Friedman Mighdoll interviews Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp, one of the great forces behind World Kid Lit. Ruth translated the charming chapter book The Invisible Elephant from Russian to English. The book is coming out next week and available for pre-orders now!

I first heard about The Invisible Elephant by Anna Anisimova, illustrated by Yulia Sidneva and translated by Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp when Paula Holmes reviewed it for us in January. In honour of the book launch in August, we are thrilled to have Ruth with us to tell us more about the joys and challenges of translating this unique picture book.

First a quick summary of the story:

For the young, blind heroine of The Invisible Elephant, the world is a thrilling place full of sounds, smells, and sensations. In four charming stories, we go with her to the zoo, the museum, and art class, and get a peek into her wonderfully magical mind where her grandfather’s walking stick can transform into a horse and a sled can become a whale. When the time comes for her to learn braille, we watch how her family and friends cheer her on as she discovers how to navigate the world in her own way.

Jackie Friedman Mighdoll: Congratulations on the upcoming launch! Can you tell us about The Invisible Elephant and its journey to you?

Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp: It was a tiny victory for blogging! The editor at Yonder (the kids’ imprint of Restless Books) first heard about the book on the Russian Kid Lit blog, a sort of spin-off project inspired by World Kid Lit. My colleague Ekaterina Shatalova wrote about the book there, and a few months later Nathan at Restless wrote to say they had acquired the rights and would I like to translate it? I think the fact that the book had been recognized by IBBY and selected for their annual selection of Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities (2017 edition) also persuaded them.

I hadn’t seen the full book until that point but immediately fell in love. As a mum to two hearing aid wearers I’m very conscious of the dearth of fun picture books with strong, feisty, fearless characters who just happen to be deaf, blind or otherwise diff-abled (differently abled). I’d love more publishers to pick up books from the IBBY recommendations.

JFM: I adore the first-person voice of the main character. She’s lively, creative, and playful. She also feels young and in love with the world. What was your translation process?

RAK: Translating picture books is so tricky because of the interplay – and sometimes ironic mismatch – between the words and the illustrations, and then there’s the irony of the mismatch between what adults say and how the protagonist interprets it. I adore Yulia’s illustrations and the way the protagonist’s inner visualisation is layered over what we see. Yulia was so patient with our requests to change the lettering, and she did a fabulous job capturing the same quirky childish handwriting style in the English lettering.

On one page the illustration and the text had to both change quite a lot, because it’s all about Russian script and the comments she makes wouldn’t make sense if carried over to a different alphabet. What was important was to convey her empathy and attachment to the letters, and her sense of pride in knowing them so well (from her fridge magnets). In the Russian version, she feels sorry for the letter Ы – it’s always inside words but never gets to be the first letter in any words. So she draws it extra big. In English, I have her feeling sorry for the letter I, which is so quick to write, he must feel rushed. So she lingers over him, giving him an extra big dot.

When translating, I copied and pasted screenshots of the pages into my document, because I wanted to always have the illustrations in mind when working on the text. It went through so many iterations, and I had incredible feedback especially from the editor Nathan Rostron and copyeditor Bryan Karetnyk. But really the most important phase was reading it aloud and listening for the intonation – did she sound frustrated where I needed her to, surprised, determined, defiant…

JFM: I noticed a lot of word play in the book. One chapter revolves around an expression ‘a lot on her plate’ where a stranger pities the main character. Ultimately, the main character re-interprets it positively! I’m assuming the expression is different in Russian.

RAK: I’m happy you noticed that phrase as it was integral to the dialogue and needed a lot of consideration!

In these stories, the protagonist is fully empowered and although she gets frustrated, she ultimately has a very happy, busy home, school and social life. So this scene towards the end is very powerful, and I think the author Anna deals with it so cleverly. The protagonist is out with Papa, sledding down a snowy and frozen river on her inflatable ‘whale’, and another little girl joins her. They’re having a whale of a time (ugh, sorry!) together until the new girl’s grandmother pulls her away abruptly, saying euphemistically, “Ей и так досталось!” This Russian phrase can mean, she’s got enough to worry about or deal with as it is, but it also has the sense of being dealt a fate in life, ie with the assumption that she means it as a difficult fate.

The protagonist is quite reasonably confused by this, but her papa deftly turns it around to being dealt a blessed hand. He says, “Конечно, досталось!” and then “Тебе очень много хорошего досталось. Смотри, какой я хороший, — это раз! Мама у нас умница, какой чай с булками сделала, — это два!” I tried so many options, but in the end settled on “Of course you’ve got enough on your plate!” and then “You have plenty of good things in your life. Look at me – that’s one! Then there’s clever Mama who’s made us yummy tea with buns – that’s two!”

The plate metaphor seemed to work so well with their wintry picnic of tea and buns, especially as the protagonist then tells her whale (the inflatable rubber ring): “Пожалуй, этого даже слишком много. Так что извини, чай с булками достанется только мне.” “That does sound like enough. Too much, even! But sorry whale, I’m the only one who gets tea and buns on my plate.” She then splashes some tea on Whale, so he gets some on his plate too. I loved how throughout the book the little girl is puzzling over the strange things adults say, and interpreting them in her own upbeat way. I’d love to open this up to students’ suggestions at a workshop one day – I’m sure they would come up with so many more creative ways of rendering this phrase. That’s the beauty of translation – so many possible directions you could go in.

JFM: As a reader, I loved the natural insight into this lively girl’s life and the way her family creates opportunities for growth and independence. In the author’s note, she discusses learning about tactile books – something that was also new for me as a reader. What did you learn as you translated this book?

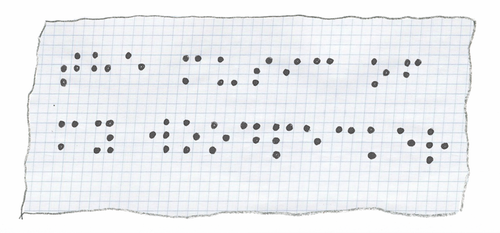

RAK: I loved learning about the tactile books she reads in her city library, and the stylus and slate she’s given to learn to read and write braille – her woodpecker. We have a beautiful book at home called SIGHT by Ukrainian book authors Romana Romanyshyn and Andriy Lesiv which was a great resource, but also opened up a fascinating rabbit hole for me as a linguist: I couldn’t resist the excuse to delve into the world of braille and its variants in Slavic and other non-Latin languages.

Another fun challenge was translating the braille in the chapter where she starts to read and write braille – rather reluctantly at first, until she realizes she can teach her friend Pasha and it can be their secret language to write notes to each other. Russian – like most Slavic languages – doesn’t have the word ‘a’ or ‘the’, so you always end up with more words in the English translation. The title of the Russian book is Музыка моего дятла (The Music of My Woodpecker – the woodpecker is her stylus for writing braille letters). This phrase appears in braille in one of the illustrations, as a sort of puzzle for readers to decode. But in English it would have been very long and cluttered, so we switched it to a new note in English braille. No spoilers!

JFM: Do you get help from anyone as you translate?

RAK: Yes, I had help from Ekaterina who wrote about the book in the first place. She’s a children’s literature scholar, a bookseller and a very experienced translator. She was able to help me unpack so much in the language. It really helped that she’s a children’s book expert and already knew the book; it’s impossible to ask someone about the text of a picture book unless they’ve also read the pictures too – really studied them – and have a feel for how the book works as a whole. It’s why translating illustrated books is so difficult – something that Daniel Hahn writes about so tantalizingly over at the New York Times.

JFM: I know you’re busy working on some big translations. Is there anything upcoming in children’s lit that you can share with us?

Yes, I’m really excited to be working on another picture book that was also featured in the IBBY Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities (which I think should be retitled something like Outstanding Books for Young People featuring Disabilities – as they are books for everyone!) There’s a new UK children’s books imprint called Pineapple Lane who are producing high-quality bilingual picture books for children displaced by conflict. The first series consisted of these gorgeous dual-language books in English and Ukrainian (all by Ukrainian authors and illustrators, and translated into English by Oksana Lushchevska). Now they’re expanding into other languages, and Marcia Lynx Qualey is helping editor Gracie source the best Arabic picture books to produce in bilingual Arabic-English editions.

They’ll be publishing Syrian author-illustrator Nadine Kaadan’s deaf-aware retelling of Rapunzel, Leila Leila, Answer Me. I first translated it about 8 years ago when the UK charity Outside In World commissioned a selection of translations of disability-inclusive children’s books, when it was included in a feature by The Guardian. Nadine has since published some beautiful books including her recent collaboration with Axel Scheffler and Renia Metallinou (The Kind Activity Book), so it’s wonderful to see this one joining her works in English.

Producing a bilingual edition is fun but of course there’s that extra layer of complexity, as structural or line edits to one language have to be made in both languages. It’s also effectively a 4-language book, because it includes lovely illustrations of Arabic sign language, which needed to be translated and checked by a British Sign Language speaker, too.

I’ll be talking more about The Invisible Elephant, and Nadine’s book Leila Leila, Answer Me, among others at a public talk called Diversity and ‘diffability’ – inclusive approaches to translating children’s literature hosted by the CIOL in September, as part of World Kid Lit Month.

Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp is a literary translator working from Arabic, German and Russian into English. She translates fiction and nonfiction, and has a particular interest in history, historical fiction, and writing for children & young adults. Her translations include books from Germany, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine, Russia, Switzerland and Syria. Ruth is a passionate advocate of world literature for young people and diversity in children’s publishing. She is co-editor of ArabKidLitNow! and Russian Kid Lit blogs, and writes about global reading for young people here at World Kid Lit and at Words Without Borders and World Literature Today.